|

Most homeowners think of solar energy this way: It's something they've heard of, it's something that's good for the environment, and it's something that has about as much bearing on them and their houses as an Alien-Broadcast Rejection System made of aluminum-foil wallpaper. But solar energy is no longer just for hippies, dippies, satellites, and remote vacation properties—it's getting mainstream.

In the last Eco-Logical, we learned about the different types of solar-energy systems and how they work. In today's article, we see how solar might be a good bet for our own houses—and can be affordable.

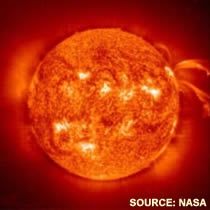

Solar power is one of the most environmentally benign energy sources available. Just 20 days

of sunshine produces the same amount of energy as everything stored in earth's reserves of oil, coal, and natural gas—yet does not come close to producing the same amount of environmental damage as even one of those options.

of sunshine produces the same amount of energy as everything stored in earth's reserves of oil, coal, and natural gas—yet does not come close to producing the same amount of environmental damage as even one of those options.

The solar energy that reaches earth can be captured and utilized in your home. One simple way is to design homes to take advantage of natural lighting during the day—opening or closing blinds and curtains to reject or allow in the sunlight, depending on whether you're in a cooling or heating cycle. Solar-energy systems can also be installed that will collect and store enough energy to heat and cool your home, heat your water, and generate electricity.

Solar collectors were very popular in the US in the early 1980s, in the aftermath of the energy crisis. Federal tax credits for residential solar collectors also helped. In 1984, 16 million square feet of collectors were sold in the United States. When fossil fuel prices dropped in the mid-1980s and

President Reagan did away with the tax credit in 1985, demand for solar collectors plummeted. In 1987, sales were down to only 4 million square feet. Most of the more than one million solar collectors sold in the 1980s were used for heating hot tubs and swimming pools.

President Reagan did away with the tax credit in 1985, demand for solar collectors plummeted. In 1987, sales were down to only 4 million square feet. Most of the more than one million solar collectors sold in the 1980s were used for heating hot tubs and swimming pools.

In other countries, solar collectors are much more common. Israel requires all new homes and apartments to use solar water heating. In Cyprus, over 90 percent of homes have solar water heaters. In the United States, the low cost of natural gas undercuts active solar water and space heaters. But in homes with electric water heaters, solar collectors make sense, saving between $250 and $500 per year.

Converting a home's electricity to run on solar power has become much more cost-effective than when the technology was first introduced. The cost of solar power has declined nearly 90 percent over the past two decades, and studies suggest that the price will continue to fall. Although the up-front costs of conversion are not insignificant—a typical household system can cost anywhere from $10,000 to $40,000—the energy generated can meet all or part of your future energy needs, lowering your utility bills and helping to pay for the initial cost of the system over time. In fact, homes that generate

more power than they need and remain connected to the energy grid may actually put that extra energy into the grid and receive a rebate from the local electric company. (Contact your utility to see if this option is available in your area.)

more power than they need and remain connected to the energy grid may actually put that extra energy into the grid and receive a rebate from the local electric company. (Contact your utility to see if this option is available in your area.)

Incentive programs also help make solar power more affordable. These programs can include personal-, sales- and property-tax incentives, rebates, grants, loans, and leasing. By taking advantage of these incentives, you could reduce the overall cost of solar power by 50 percent or more. DSIRE—the Database of State Incentives for Renewable Energy—offers a comprehensive listing of state and local programs, as well as incentives offered by specific utilities.

Maybe your previous thoughts about all things solar have naturally leaned towards a plan to slather on some Minus-10 suntan lotion and try to get into the Hamilton Book of Tanning Records for "Most Days in a Row of Being Sun-Dazed." But from an energy perspective, the sun is well worth worshiping.

|