|

Hey, we heard a rumor that gas stations will soon be installing systems to vacuum your car and your wallet at the same time. Yeay efficiency!

Most of us are aware that

high gasoline prices are a problem these days. Many people may also be aware that the price of a barrel of crude oil is also quite high. We have a tendency to try to put the blame for these petroleum miseries on hateful

oil-producing nations; greedy oil companies and manipulative commodities traders; rising consumption in China and other developing countries; or maybe even on environmentalists who attempt to thwart extraction of new sources of oil in wilderness areas.

oil-producing nations; greedy oil companies and manipulative commodities traders; rising consumption in China and other developing countries; or maybe even on environmentalists who attempt to thwart extraction of new sources of oil in wilderness areas.

To be fair, there are some effects from all of these factors, but the much larger truth is that global petroleum supplies have gotten very tight relative to demand. For the most part, today's oil prices simply reflect the law of supply and demand. But that's just the tip of the problem. The real story is about "peak oil"—the point in history when global petroleum production will peak—forever. Once oil supply can no longer keep up with oil demand, an economic shockwave will hit us and wreak havoc with our modern economies, which rely on abundant oil to support never-ending growth.

The official line from our political leaders and government scientists is that there's enough remaining oil that the peak won't hit for several decades. Many geologists and other people who study the field think the evidence says we are at peak now or will be there within just a few years. That certainly sounds a lot scarier.

Today we have a basic peak oil article—a primer on the subject. It's the first of a two-part series adapted from the works of Richard Heinberg, a journalist, educator, and author, and one of the world's foremost thinkers about the coming impacts of peak oil. Part 1 presents the evidence that peak oil will hit us sooner rather than later. Part 2 — US Oil Wars — lays bare the current approach of trying to use military dominance to ensure a continuing supply of petroleum in this country. Part 2 also describes some better options for dealing with the end of the oil age.

~ ~ ~

Peak Oil and Options for a Post-Carbon World, pt 1

by Richard Heinberg

Peak Oil and Options for a Post-Carbon World, pt 1

by Richard Heinberg

It's important that we have an accurate picture of where we are relative to peak oil so we can take actions that make sense and can have some effect, given the context.

There is an approaching "perfect storm" of global problems that we will be facing over the next couple of decades, including:

- a peak in global oil production ("peak oil");

- continued population growth;

- declining per capita food production;

- climate change, pollution, habitat destruction, loss of biodiversity;

- unsustainable levels of US debt;

- international political instability.

This article will deal mostly with peak oil, but some of the other issues are relevant.

Over the last century, we have used oil to increase the carrying capacity of planet earth and increase our population:

- We've used petroleum-derived products, oil-powered groundwater extraction and irrigation, and oil-powered machinery to create "industrial agriculture" and greatly increase the human food supply.

- We use oil-powered vehicles to carry resources from where they're abundant to where they're scarce so that we can, for instance, build cities in the middle of deserts, where people really shouldn't be living.

We have increased the global human population by over 500% in just the last 150 years. We were at fewer than 1 billion in 1800 (toward the beginning of the Industrial Revolution), and we passed 6 billion in the 1998-1999 timeframe. In the next half-decade after that, we added another 400 million—essentially a North America's worth of people. Unfortunately, we haven't added another North America's worth of resources or support infrastructure.

The rate of population growth is beginning to taper off, but the overall numbers are very worrisome, given the fact that per capita food production is declining. The reasons for the decline include:

- Decline in amount of arable land — We had been increasing the amount of farm land by clearing forests and irrigating dry land, but that strategy has reached a point of diminishing returns. Today we are paving over farm land and losing acreage in some areas to soil salinization and erosion.

- Green Revolution burnout — The great yield enhancements achieved through the use of chemical pesticides, fertilizers, and increased irrigation have peaked. In some cases, yields are starting to decline again.

- Collapse of ocean fisheries — Many ocean fisheries are near collapse or have collapsed.

|

Environmental problems like global warming are likely to exacerbate food production problems. The high levels of US debt and inherent economic instability will mean there won't be a lot of free-flowing cash available to fix these problems once they become more obvious to everyone.

|

RELATED GP ARTICLE

|

|

NOW PLAYING:

THE DIRTY BAKER’S DOZEN

13 Factors in the Coming

Food Crisis

|

|

America, which today has become notorious as the world's biggest importer of oil, actually still produces much of its own oil. In fact, it is still the world's third largest oil producer. Moreover, it was once the world's largest exporter of oil. But, oh, how times have changed. The chart below compares some of the characteristics of the US in 1950 and today.

| |

|

| |

World's foremost oil producer and oil exporter |

World's foremost oil importer |

|

| |

World's largest exporter of machine tools and manufactured goods |

World's largest importer of manufactured goods, with manufacturing jobs now fleeing to other countries |

|

| |

Self-sufficient in nearly all resources |

World's foremost importer of non-petroleum resources |

|

| |

World's foremost creditor nation |

World's foremost debtor nation |

|

Much of this is certainly the result of bad management over the last several decades, but much of the cause is rooted in the depletion of US reserves of the resource that made the United States the most powerful nation in history—oil.

|

When it comes to oil, the US is the most explored place on the planet. More oil wells have been drilled in the continental US than in the rest of the world. So, if you want to understand the oil industry, petroleum geology, and how it's going to go globally, the experiences in the US can be seen as a template.

|

|

DEFINITIONS |

|

Oil discovery — the identification of new oil reserves (but without extracting them from the ground)

Oil extraction / oil production — the removal of oil from the ground for conversion into fuels and other products

|

|

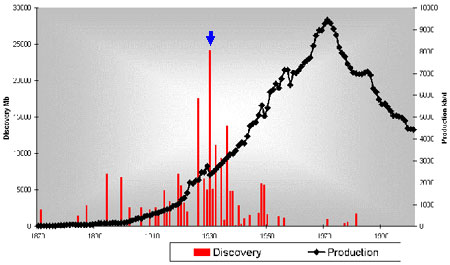

Figure 1 shows that US oil discoveries peaked around 1930 (blue arrow), with the discovery of huge oil deposits in eastern Texas. But discovery of new oil then began to decline very quickly, and very little oil is being discovered in the US today. With the exception of relatively small amounts of oil in Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico, experts have largely concluded that it's simply not worth investing any more money in the hunt for new oil in the US.

Figure 1. U.S. Oil Discovery and Oil Production

About 40 years after the US hit its oil-discovery peak, the country hit its oil-production peak (in 1971). The US discovery peak had been successfully predicted (to within 12 months) 14 years earlier by geologist M. King Hubbert.

|

The phenomenon of oil-extraction peaks has been well studied by now. There are several factors that relate to the physical and economic practicality of getting oil out of the ground at any particular location:

- Oil deposits vary in quality (grade of oil), which affects how easily the oil can be refined.

- There are different levels of difficulty for extracting a given field of oil from its surrounding geological formations.

Different levels of effort and energy are required to extract oil from various oil fields; thus, the economics of oil extraction vary from field to field. On the oil-refining side, poor-quality oil is harder to convert into useful products like gasoline.

In any given region, it's natural to first go after the "easy oil"—the best quality oil in the most easily extracted locations and geological formations. After about the first half of the oil has been extracted, what remains gets more difficult to extract, and the rate of extraction hits a peak and then begins to decline.

|

|

DRILL, DRILL, DRILL |

|

There is a resurgence of drilling fever in the US, with coastal areas and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge the primary targets. Much controversy surrounds these proposals. Supply-siders say "we must drill!"; environmentalists say "we must not!"

Over the long run, it is possible that these new sources could bring about 2 million barrels per day (MBD) online. That's a significant amount, but remember, that would be a maximum production rate lasting only for a few years and would occur until the middle of the next decade. Prior to and after the peak production years, actual flow rates would be much less than 2 MBD.

Still, this additional amount of oil would be substantial over the lifespans of the fields. Unfortunately, declines in other (current) fields over that same period would more than wipe out the gains from the new fields.

A bigger problem is that the US uses about 25% of the world's oil production—with 2/3 of that imported—but has only 2% of estimated global oil reserves. That's math that won't work, now, next decade, or ever—no matter how much new domestic drilling we take on.

To be clear, we at GP are not saying we shouldn't drill in ANWR and off the coasts. We are saying that doing so will not fix our peak oil problem—let alone free us from imported oil. It might even be worth considering whether it would be smart to leave that oil in the ground for the day when it's worth $400 a barrel.

-- Grinning Planet

|

|

The actual peak of the extraction rate for a given field can vary slightly relative to what percentage of the field's oil remains, but the bell-shaped curve used to represent oil extraction rates seems to have held true for every oil reservoir, oil region, and oil-producing country—and will undoubtedly hold true for the world as a whole. The only question is exactly when the global production peak will occur.

Figure 2 shows actual and projected petroleum production, by region. One can see the contraction of oil use in the late 1970s and early 1980s (blue arrow) as a result of the OPEC embargo, price shocks, and subsequent conservation measures. Since the mid-1980s, demand and production have recovered and soared.

Several top analysts estimate that peak will occur in 2011-2012 (red arrow), with only minor production increases between now and then. A few even say the peak already occurred—in 2005/2006—with total "oil" production since then having seen minor increases because of increases in non-petroleum liquids production.

Figure 2. Global Oil Production

Chris Skrebowski, a consulting editor for Petroleum Review and a researcher for the Energy Institute in Britain, has noted the alarming falloff in discoveries of large oil fields (from which a majority of the world's crude flows). Skrebowski notes that "we would probably have to go back to the early 1920s to find a year when fewer large oil discoveries were made." Skrebowski is currently predicted that the global oil supply will peak in 2011 or 2012.

|

It is widely accepted that global oil discoveries peaked in 1963-64. If we remember that the lag time between the peak in US oil discovery and the peak in US oil production was 40 years, we can use that as a rough predictor of when the global oil-production peak will hit, and it predicts the peak will be soon.

|

|

DRAWING DOWN |

|

At this point, we are now extracting about 5 times as much oil each year as we discover.

|

|

|

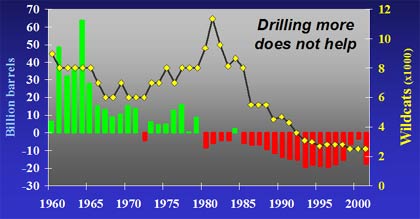

In Figure 3, the green bars show that up until 1980, the world was discovering more new oil deposits than it was using in production, and thereafter (the red bars) the world began eating into its reserves to meet demand. The black line with the yellow dots plots the number of wildcat wells being sunk in search of new oil. It shows that industry responded to the declining discoveries in the 1970s and early 1980s by sharply increasing their drilling efforts—until they figured out that the additional drilling was not producing results.

|

|

A FIT OF PEAK |

|

Of the 65 largest oil producing countries in the world, 54 are past their production peaks.

|

|

Figure 3. Net Oil Discovery Minus Production

Some economists predict that peak oil is still far away because rising oil prices rise will provide incentive for oil companies to go out and find additional oil. This data calls such claims into question—there may not be that much oil out there to find! And even with today's record-high oil prices, the last few years have not seen any significant increases in production.

There is no question that more oil will be found in the future, but it's likely to be smaller fields and oil of lower quality.

The International Energy Agency (IEA), which is sort of the global equivalent of the US Department of Energy, tends to be very optimistic in its oil projections. But even they are now revising future-production estimates drastically downward and noting that even moderate production increases will only happen with significantly higher levels of investment.

|

Some of the reasons the IEA gives for predicting future problems are:

- we've already captured much of the "low-hanging" fruit (the "easy oil");

- older oil fields are mature and declining;

- new discoveries are smaller fields;

- the oil industry is extracting oil from fields more quickly;

- more effort is being expended just to offset oil depletions;

- global reserves have been overstated for political reasons.

The last point about declared oil reserves being overstated is worth looking at further. The reason that OPEC countries have done this is that, under OPEC rules, member countries have previously been allowed to export oil based on their level of stated reserves. This created an incentive for OPEC countries that wished to boost their exports to over-report their reserves.

|

|

QUOTH THE MAVEN |

|

In 2003, Jon Thompson, president of ExxonMobil, stated:

"We estimate that world oil and gas production from existing fields is declining at an average rate of about 4 to 6 percent a year. To meet projected demand in 2015, the industry will have to add about 100 million oil-equivalent barrels a day of new production. That's equal to about 80 percent of today's production level. In other words, by 2015, we will need to find, develop and produce a volume of new oil and gas that is equal to 8 out of every 10 barrels being produced today. In addition, the cost associated with providing this additional oil and gas is expected to be considerably more than what industry is now spending."

The world is far off pace Thompson said would be required for supply to keep up with demand.

|

|

Another measure of OPEC's ability to meet higher oil demand in the future is spare production capacity—how much they could ramp up production if they wanted to. The IEA notes that since late 2002, spare oil production capacity has been below the 3-4 MBD that has traditionally been regarded by many analysts as a key barometer of market tightness, and well below the average levels of spare capacity evident in the past decade. OPEC's spare production capacity is now nearly non-existent—they are currently producing almost flat-out from their existing wells.

~ ~ ~

|

This is some pretty convincing evidence that the oil crunch—and side effects like higher gas prices—are likely to continue to worsen. And because our current lifestyles, level of prosperity, population, and food production are all tied to the availability of cheap oil, the arrival of peak oil could produce a disastrous economic shock. High gas prices may turn out to be a very minor problem, comparatively.

|

|

Richard Heinberg is a journalist, educator, and analyst. He has lectured internationally and is widely respected as one of our most clear-headed thinkers about energy issues and their impact on economies and societies.

For more Richard Heinberg:

-- Books

-- Museletter

(monthly newsletter)

|

|

|

In Part 2 of this series, we present two very different scenarios for moving forward into the post-petroleum world: US Oil Wars or Adaptation.

|

Know someone who might find this peak oil article interesting?

Please send it to them

Books, articles, and resources:

Get Grinning Planet free via email

|

| |

ARTICLES IN THIS SERIES

|

| |

|

1. Peak Oil Article

2. US Oil War -- or Adaptation?

3. Peak Oil and Politics (Spring 2009)

This is Part 1 of a three-part series. The final piece will be published later in 2008. Why not sign up for the free GP email service so you don't miss it.

|

| |

|

|