|

In a previous Peak Oil article, we presented compelling evidence that a peak in global oil production will likely occur within the next few years. Because the global economy, including our food-production and transportation systems are heavily reliant on cheap oil, once oil production can no longer keep up with oil demand, serious economic shockwaves are sure to be felt.

Our leaders aren't saying much about this problem, but evidence suggests that they do understand it. For the US, oil wars appear to be the new energy policy. Oil and war are both profitable, but beyond that, our well-invested leaders have a political and financial interest in maintaining a worry-free version of an oil-dependent, consumerist economy for as long as possible. Once everyone realizes the truth about peak oil and its impacts, a great deal of (less profitable) chaos is likely to ensue.

In today's article, we offer Part 2 of our adapted works from Richard Heinberg, one of the world's leading thinkers on the impacts of energy descent. We'll briefly discuss the evidence for "the US oil war," followed by some better options for dealing with the end of the oil age. Much of the material comes from Heinberg's presentations and writings; some of it is sourced directly from Grinning Planet.

~ ~ ~

Peak Oil and Options for a Post-Carbon World,

pt 2

by Richard Heinberg

Peak Oil and Options for a Post-Carbon World,

pt 2

by Richard Heinberg

To lay the groundwork for talking about how we move forward in the post-peak-oil world, we should first review where the planet's remaining oil reserves are (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of Proved Oil Reserves at End

The bar for the Middle East's reserves should probably be about 1/3 shorter than it is due to overly optimistic statements of reserves from Middle Eastern OPEC nations (who overstate their reserves to be able to export more oil and still stay within OPEC rules). But even given that, the Middle East still has a lot of the world's remaining oil.

As you will see, the location of global oil reserves has much to do with political decisions today and in the future. Let's explore the various possible ways forward in dealing with peak oil.

Simply put, the "Last One Standing" approach to declining oil availability is to use the military prowess of the United States to ensure we have our needed share of the remaining oil. That may initially seem like a wild overstatement of reality, but consider the following.

In late 1999, Dick Cheney, then chairman of the world's largest oil services company, Halliburton, spoke before the International Petroleum Institute in London. He presented the following picture of world oil supply and demand to industry insiders:

"By some estimates, there will be an average of two percent annual growth in global oil demand over the years ahead, along with, conservatively, a three percent natural decline in production from existing reserves ... That means by 2010, we will need on the order of an additional fifty million barrels a day."

This statement is consistent with what the International Energy Agency (IEA) and many oil-industry insiders have been saying. It's important to realize that 50 million barrels a day is five times Saudi Arabia's current output.

So, Cheney had every reason to know in advance that by the middle of the 2000's, the US would be suffering the effects of tightening oil supplies. One of his first actions upon taking office in 2001 was to convene an Energy Task Force, a secretive body whose only publicly released documents consist largely of information on the oil-producing fields of Iraq and neighboring countries. Cheney has stated publicly that energy conservation may be a sign of personal virtue but is not the basis for an energy policy. George W. Bush has stated publicly that the US way of life is not negotiable. Cheney has also said that we likely face war for the remainder of our lifetimes. For the US, oil wars appear to be our energy plan going forward.

Oil Wars — Where, Why, and Who?

What types of war-for-oil conflict are we likely to see?

1. Conflicts between rich consuming nations and poorer producing nations:

There may be conflicts between oil-importing nations and oil-exporting nations when a powerful oil-importing nation deems an oil-exporting nation to have an "unacceptable" political regime.

We now know that false reasons were given for the US invasion of Iraq. There is copious evidence, including statements by former administration insiders like Paul O'Neil and Alan Greenspan, that Iraq was about oil all along. Afghanistan, to a lesser extent, fits this US oil-war strategy as well, given its strategic positioning for a pipeline pass-through.

Iran and Venezuela are potential targets for future US oil wars. Note the never-ending US rhetoric against both countries, and note that Iran, Iraq, and Venezuela are all in the Top 10 for global oil reserves.

2. Conflicts between consuming nations:

Using their large piles of US dollars, China has been locking up long-term oil contracts in Central Asia, the Middle East and elsewhere. Saudi Arabia, interestingly, has given almost all of their recent long-term oil contracts to China rather than the US. As you can imagine, this has bothered some US-based oil companies.

Does the Saudi action have to do with the fact that China is not currently invading one of its neighbors? Does it have to do with the Saudis having more faith in the Chinese economy? Remember that in Part 1 we talked about record levels of US debt (much of it now held by China), record US trade deficits (much of it with China), and high levels of US dependence on imported oil, resources, and manufactured products. There is a strange sort of dance of mutual dependence and competition playing out between China and the US, but what happens once we hit the other side of peak oil, when there is no longer enough oil to meet the demands of both economies? Will tensions rise?

Tensions are already rising between the US and Russia in central Asia. Official statements are careful to talk only about geopolitics—aggression on the part of the other side and protection of sovereign or democratic interests by the home team—but the truth is that this region is a key area for controlling the flow of oil and natural gas westward and as a military staging area related to critical countries like Iran.

3. Civil wars within producing nations for control of resources:

Civil wars will occur within oil-producing nations to gain control of power and resources. We saw this in Venezuela several years ago and more recently in Nigeria and Iraq. We're increasingly likely to see it in other Middle Eastern nations in the future, as the totalitarian governments supported by the West (in exchange for favorable treatment on oil supplies) begin to lose control over those they rule.

4. Asymmetrical warfare:

Asymmetrical warfare—otherwise known as terrorism—may be increasingly likely between rich oil-consuming nations and non-state entities in oil-producing nations.

All of this is in our future. These may not all be shooting wars, or at least they may not start out that way.

The U.S. Energy Picture

I am a passionate advocate for alternative energy sources, particularly renewable ones. But we have to take into account where we are with respect to those resources.

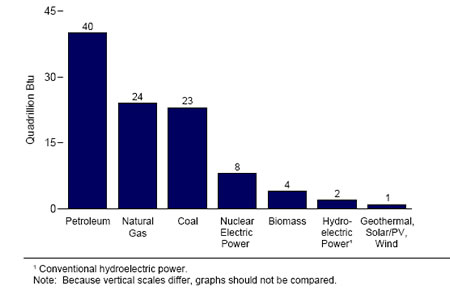

As you can see in Figure 2, fossil fuels are currently the largest part of our energy budget.

Figure 2.

U.S. Energy Consumption By Source

Figure 2 also shows renewable energy to be a very small part of the picture. Geothermal is about 0.3% of the energy mix, with solar PV and wind representing about 0.4% combined. If we were to somehow quadruple our use of solar and wind energy over the next few years---which would require a huge effort---solar and wind would still be at less than 2% of our national energy budget.

|

The current investment pattern—a billion dollars here and a billion dollars there for alternative-energy research and for things like tax credits so people will put solar panels on their roofs—won't get us there. We need to be investing hundreds of billions of dollars a year to develop the technologies necessary to overcome our dependence on vanishing fossil fuels. Overall, this effort will require the investment of trillions of dollars. Unfortunately, this is not on the drawing boards.

|

|

I THOUGHT WE WERE TALKING ABOUT OIL!

|

|

What's the connection between peak oil, diminishing supplies of other fossil fuels (like natural gas), and the need for more electricity-generating technologies like solar and wind? If the cars of the future are be plug-in hybrids or full-electric vehicles, a significant increase in electricity generation will be required. Similarly, if our future cars are going to run on hydrogen—this is less likely, but perhaps is a possibility for a few decades from now—the current practice of generating hydrogen from coal or natural gas will likely have to be replaced with electricity-driven hydrolysis. Either way, more juice flowing through the wires is going to be necessary.

— Grinning Planet

|

|

Can the “Hydrogen Economy” Save Us?

Some people are pushing the idea of a "hydrogen economy"; in particular, that we can convert from oil-powered vehicles to hydrogen-powered vehicles. Will this save us? Not likely.

First, realize that hydrogen is a way to store energy; it's not an energy source. And while hydrogen fuel cells are very efficient, the inefficiencies of hydrogen production, transportation, and storage would more than negate the efficiency gains from fuel cells. Also, at current levels of technology, batteries are actually a more efficient way to store energy. Today's fuel cell prototypes are very expensive, they wear out quickly, and are not widely available.

Today, most hydrogen is made from fossil fuels, especially natural gas, supplies of which are growing increasingly tight in North America. Making hydrogen from water using electrolysis is expensive because it requires large amounts of electricity (which is why the coal and nuclear industries support the idea of a hydrogen economy). In addition to the hydrogen production challenges, there are significant problems to overcome with hydrogen storage.

To a great extent, federally funded fuel cell research is a boondoggle for the auto companies. For a while, the hydrogen myth provided them with temporary cover from attempts to raise fuel economy standards (which can help address fuel consumption). The recently passed mileage standard is a good step (though notably lacking in ambition), but the delay in getting around to it is very unfortunate. With a vehicle fleet turnover rate of more than 16 years, it will take well more than a decade to fully reach the new efficiency targets.

Spending money on hydrogen research takes investment capital away from the development of renewable energy sources or conservation measures that can realistically be deployed in the near- and mid-term—when peak oil is likely to hit, and long before the much ballyhooed hydrogen economy has any hope of making a dent.

Addressing Transportation Efficiency

So, what are we to do? We're going to have to look not only at supply-side solutions, but also at demand-side solutions. We have to look first at transportation because that's where we are most dependent on fossil fuels. Close to 100% of our transportation energy is coming from oil.

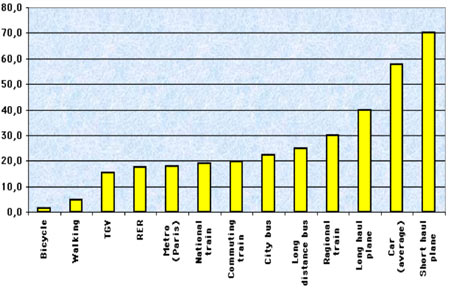

Figure 3 compares the energy consumption associated with various modes of transportation over a unit distance. The taller the yellow bar, the less efficient the mode of transportation. We see that bicycling is the most efficient mode of travel, and personal automobiles are just about the least. In between driving cars and bicycling are a variety of mass transit modes, including subways, trains, and buses. We need to start moving away from our dependence on the most inefficient and oil-dependent transportation modes (longer yellow bars) and towards transportation modes that are more efficient and less oil-dependent (shorter yellow bars). Europe is already far ahead of the US in this regard.

Figure 3.

Energy Consumption vs. Distance Traveled

for Various Modes of Transportation

In America, we're addicted to the personal automobile; it's seen almost as a birthright. We've based our whole way of life—our suburban infrastructure—on the car. But this is a luxury that will be impossible to maintain after the effects of peak oil hit, and we have to develop strategies for deemphasizing the personal automobile.

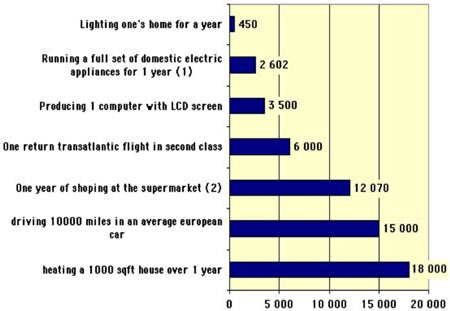

Transportation is not the only thing we use a lot of energy for, as you can see in Figure 4. The energy associated with food production and home heating is also quite high.

Figure 4.

Energy Consumption by Activity

Turning off lights when not in use or replacing incandescent bulbs with compact fluorescents is a good idea, but compare the amount of energy used for the lighting category to any of the others. We have to be strategic about where we try to save energy. We have to look at the biggest energy-use categories first—food production, transportation, and home heating. We have to find alternative energy sources, but we will also have to change our way of life.

Americans usually meet suggestions that we change our way of life with eye rolls (or worse). As mentioned earlier, the US president has stated that the American way of life is not negotiable. If we take that approach, though, what goes with it will be oil wars—fighting for the remainder of our lifetimes for the last drop. A number of countries around the world, including the US, have weapons that are capable of ending higher life on the planet. Humanity has managed to not use them yet, but what happens when people are starving? I would rather not go down that road.

Challenges and Solutions for Civilizations

What we really must do is address the underlying ecological dilemma—resource depletion, habitat destruction, and population pressure. Throughout human history, civilizations have faced these problems, and the depletion of oil and the rest of our woes today are little different.

Here are some of the solutions that have been used in the past to address resource depletion, habitat destruction, and population pressure, with comments about how they might or might not work now.

1. Move elsewhere

For tens of thousands of years, we've been moving into new territories that have new resources. We started in Africa, and now we've covered the globe with human beings. We have inhabited every possible place.

2. Exploit existing resources more intensively

You can exploit existing resources more intensively, but there are limits. For instance, with food production we first benefited from horticulture, then agriculture, and most recently industrial agriculture and high-tech commercial fishing. But we're to the point where we can't exploit resources like ocean fisheries, topsoil, and fresh water (as well as oil and natural gas) much more intensively than we already are.

3. Find new resources

|

Our genius as a species is that we have found ways to develop new resources—to essentially implement supply-side solutions to the ecological dilemma. We've done this far better than any other species. However, the problem with supply-side solutions is that they are subject to diminishing returns over time. And that is the problem we face now—a reliance on the approach of ever-increasing our supplies to support an ever-increasing population. Sooner or later, we will have to address the problem from the demand side of the equation.

|

|

THE FIX IS IN |

|

Will there be some sort of technological fix—the hydrogen economy, methane hydrates, or car makers suddenly producing a car that gets 200 miles per gallon? Perhaps, but I wouldn't want to bet on that.

— Richard Heinberg

|

|

4. Limit population

Limiting population is a prime way to limit demand. I don't mean killing people off; I mean reducing the population slowly by reducing the human birth rate in humane ways—through education, human rights improvements, and access to family planning, without the imposition of authoritarian rules.

5. Limit resource use

The other way to limit demand is to put limitations on resource use. This would necessarily have to start with the wealthy countries, where most of the resource use is occurring. Though unpalatable to most people's current thinking, some form of rationing or usage control may be preferable to the chaos associated with constant shortages. On a broad scale, an "oil depletion protocol" could serve to give nations a common framework they can use to manage their voluntary transition away from oil in an orderly, planned fashion.

6. Die off

If none of 1 through 5 can be achieved, we will, at some point, die off to a population level that is sustainable, given available energy and resources.

Wake-Up Call for the U.S.—

Oil Wars Are Not the Way to Go

What's called for here is intelligence. We pride ourselves on being an intelligent species. The one way that we could prove it is by demonstrating that we correctly perceive this problem and its solutions, and changing our behavior accordingly. It's as simple as that.

Here are the things to focus on:

- Aim for maximum efficiency — invest more in increasing efficiency.

- Localize and decentralize — for instance, reverse the trend of globalization, which will reduce transportation requirements.

- Use alternatives now — incentivize people and markets to get alternative solutions working now, not later.

- Use less — everything requires energy to be built and transported (and usually to be used too), so buying and using less stuff uses less energy.

- Raise awareness — talk about the issue!

We must ensure local water security and local food security. We must reduce our need for transportation. We have to support our local economies and foster local manufacturing of essential goods. (Do you know who made your shoes?)

|

This is a challenging picture. The majority of Americans probably won't change or even listen. But we need a small, core portion of society that understands the reasons for the tough things that are going to be happening over the next decades, and that understands how to respond. If these people can start dealing with the problem in their own lives and can start making changes in their local communities, they can teach others. Then there is hope.

|

|

Richard Heinberg is a journalist, educator, and analyst. He has lectured internationally and is widely respected as one of our most clear-headed thinkers about energy issues and their impact on economies and societies.

For more Richard Heinberg:

-- Books

-- Museletter

(monthly newsletter)

|

|

|

Thanks to Richard Heinberg for his tireless efforts to educate us all about peak oil and the tough choices we face.

|

It occurred to us that one of the reasons it's so hard for society to get traction on Peak Oil is that our elected leaders are largely silent on the subject. In a future issue of Grinning Planet, we'll explore this angle in a new article: "Peak Oil and Politics"...

Know someone who might like this article about US oil wars? Please forward it to them.

Books, articles, and resources:

Get Grinning Planet

free via email

|

| |

ARTICLES IN THIS SERIES

|

| |

|

1. Peak Oil Article

2. US Oil Wars (or Adaptation?)

3. Peak Oil and Politics (Spring 2009)

This is Part 2 of a three-part series. The final piece will be published in the first part of 2009. Why not sign up for the free GP email service so you don't miss it.

|

| |

| |

RELATED GP ARTICLES

|

| |

|

TRADING IN DINOSAUR POWER ON A BETTER MODEL

Peak Oil Solutions

— Real Energy Solutions for Declining Energy Supplies

A FAMOUS WESTERN LAST LINE: “SHALE ... SHALE ... COME BACK!”

Oil Shale Problems

Mean It Will Not Save the U.S. from Oil Shortages

THIRD TIME’S THE CHARMIN

Increase Your

Food Security

— and Save Money and Improve Nutritional Intake

|

| |

|

|